Many internet freedom advocates agree that women and sexual minorities are victims of harassment, doxing, revenge porn, and other pervasive forms of online gender-based violence. However, we are yet to fully understand the impact online gender-based violence has on women in Africa. Currently, there is a lack of robust baseline data coupled with insufficient legal and policy protections in many countries across the continent. Often, this leads to a detachment from the culpability of internet platforms and their failing redress mechanism.

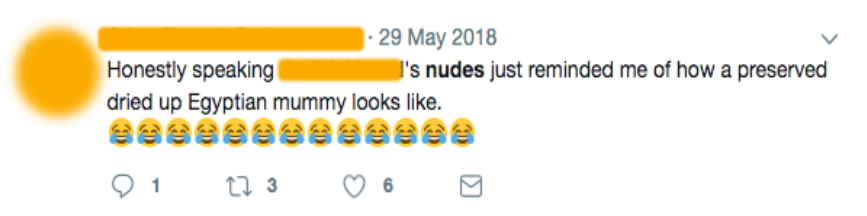

Online Responses to Non-Consensual Sharing of Personal Images

In a small, recent survey conducted by Pollicy in Uganda, twenty-two percent of women surveyed claimed to have been a victim of cyberbullying, whereas 12% of women were unsure. The survey went on to ask women who had been victims of cyberbullying how they responded to the situation. 22% responded that they ignored their perpetrator while 37% said that they blocked them. 13% reacted by changing their phone number or accounts altogether. Only 5% of victims reported the matter to the police.

More women are online now than ever before.

Private information, such as photos and videos, is leaked onto social media without women’s consent. Women are often victims of harassment, stalking, and cyberbullying but the extent of this violence is unknown as most cases go unreported. In a bizarre turn of events, women who have been victims of revenge porn have been arrested under the orders of the Minister of Ethics in Uganda.

Our research seeks to inform evidence-based policy to push for digital equality: we want to understand the prevalence and responses to online-based violence against women in selected Africa countries. These countries rank higher on indices for democracy, high internet coverage and relevant/active online communities. We will supplement this baseline understanding by looking at the existing and/or lacking legal and policy protections afforded to women and look at the accountability and redress mechanism provided by platforms and social media sites to cases coming from these countries.

The International Center for Research on Women has created a conceptual framework of technology-facilitated GBV which will be useful in guiding our discussions moving forward.

As part of our ongoing work on understanding and working within the data ecosystem, data protection, and digital rights, we developed 5 main research questions.

Our Research Questions:

- What is the online experience for women living in the case countries?

- How prevalent is online gender-based violence in the case study countries?

- What policies and laws exist to protect women and sexual minorities in these countries?

- How do social media platforms and intermediaries respond to online gender-based violence against the group in these countries?

- What practices do women in these countries undertake to tackle issues of online GBV?

Given the growing reach of the internet on African content, over the past few years, there has been increased discussion about online gender-based violence, especially on social media. In order to understand online GBV, we need to view this violence on a continuum rather than as isolated incidents removed from existing structural frameworks. Discriminatory gendered practices that are shaped by social, economic, cultural, and political structures in the physical world are similarly reproduced online across digital platforms.

Most research studies available focus on heterosexual, in-school adolescents and youth, primarily in high-income countries, leaving wide gaps in knowledge, especially on how it affects women around the African continent. Estimates to online GBV range from 10–45% across multiple African countries, 33% in Kenya, and 45.5% on average in Francophone Africa. Interestingly, the Web Foundation further states that in cities with the lowest internet access rates among women, namely Nairobi and Kampala, there tended to be higher rates of online GBV which could be a factor inhibiting women’s access to the internet.

Most, if not all, countries across the continent do not have specific legislation against technology-facilitated online GBV. Taking the example of South Africa, responses are dependent on existing pieces of legislation, common-law definitions of criminal offenses, and civil law remedies. Cases on cyberbullying may fall under laws such as Protection from Harassment Act 17 of 2011 (Republic of South Africa, 2011), Electronic Communications and Transactions Act 25 of 2002 (the ECT Act) (Republic of South Africa, 2002), Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 (Republic of South Africa, 1977) or even under the Films and Publications Act 65 of 1996 (Republic of South Africa, 1996b) in cases of non-consensual pornography. There are no existing preventive measures to specifically target online GBV. While some countries, mostly outside Africa, have attempted to address online violence, the enforcement of such measures has proven tricky due to a lack of appropriate mechanisms, procedures, and capacity.

Online platforms provide little to no remedial measures for victims of online GBV. A report by Amnesty International claims that Twitter allows violence against women to flourish on their platforms by inadequately investigating and responding to reports of harassment. Impunity for both primary and secondary perpetrators of online GBV introduces complexity between online violence, legal frameworks, and technology platforms. Violence against women online is often trivialized with poor punitive action taken by authorities.

Feminist Principles of the Internet

The Feminist Principles of the Internet (FPI) are a set of statements that provide a framework for women’s movements to articulate and explore issues related to technology (source: feministinternet.org). They offer a gender and sexual rights lens on critical internet-related rights. The FPI have been organized into 5 clusters, with 17 Principles in total.

#ImagineaFeministInternet

The Feminist Internet Research Network

The Feminist Internet Research Network focuses on the making of a feminist internet is critical to bring about transformation in gendered structures of power that exist online and on the ground.

Feminist scholars contend that when studying technology and gender, it is essential to note that technology and gender are not mutually exclusive but “co-produced”. Technology and gender relations do not exist in a vacuum: technology is shaped by the environment it exists in; it serves the purpose it does because humans built it in that way; the social structures that dictate gender relations also govern technology. In-turn, prevailing gender construction determine who designs the technology, the purpose it serves, who builds and develops, manufactures, and uses it; moreover, this relationship of co-production is continuously changing each other, and this process does not stop just with the production of technology but extends to design, the use of technology and the content it provides. Therefore, technology and gender dynamically influence each other.

For this research, we will be engaging with African Feminist thinking. First, we acknowledge that there are many African feminisms and each country/region within the continent may have a localized framework while at the same time sharing many commonalities. This is the first and important step in how we contextualize our research to each country and region.

Considering intersectionality, we understand that each context has very different languages, but also cultural and traditional norms, that we intend to incorporate into our research and understanding. For example, issues such as tribe, language, age, and education largely influence positions of political and economic power. In South Africa, similar issues in addition to race determine who is at the bottom of the power dynamics. One major way to incorporate this aspect of our framework is to hold focus group discussions prior to the quantitative surveys to understand how each region views, describes, and conceptualizes what online GBV is.

African feminists understand and assume this responsibility towards striving for just and equal societies. This is a major aim of this research in understanding how online GBV affects women, restricts women, and directly influences how women can benefit from online access and spaces, and then what it would take to level the playing field for men and women, given that women continue to lag behind in technology spaces.

Third, art and love are viewed within African Feminism as radically transformative acts. We understand that a majority of our participants and intended audiences may never aim to read a report on GBV but we hope to reach them with this information on their experiences in creative ways through art and similar media. As Minna Salami states in her piece, 7 key issues in African feminist thought, “African feminist thought is fuelled by the idea that love and justice are complementary to revolution and change. It is focused on healing, reconciliation, and on an insistence that the language of African womanhood, from its global position, is the language that can transform society into one where sexual, racial, spiritual, psychological and social equality is afforded.”

Collaboration

We are excited to bring this research into reality and are looking to partner with any organizations interested in collaborating to create a feminist internet.

Please reach out to us at info@pollicy.org or visit our website: Digital Rights Africa.

Written by Neema Iyer, Founder at Pollicy

Leave A Comment